Metro Philadelphia has commonly been characterized as stable by multifamily investors. It’s akin to a backhanded compliment when comparing our region to those with higher population growth or more “business-friendly” governments. Cue the overused “eds and meds” story that fails to reference the technology, life sciences or gene therapy industries, all of which help to diversify the region’s employment base and contribute to a strong economy. (The “eds,” of course, are institutions of higher learning and the “meds” are medical facilities.)

Historically, investors also haven’t differentiated between suburban Philadelphia, namely the surrounding counties, and the City of Philadelphia. They’ve grouped our metro region into one giant oversimplification. However, recently we’ve begun to see an unmistakable divergence in fundamentals between the city and the suburbs. As a result, when multifamily investors speak about opportunities in Philadelphia today, they are making clear distinctions between the suburbs and the city.

A Study in Contrasts

The greater Philadelphia multifamily landscape has become a tale of two divergent markets. Property fundamentals in the suburbs remain healthy, with steady rent growth and high occupancy levels. Long-term demographic trends and an undersupply of housing have investors optimistic about investing in the suburbs.

Unlike the wave of new construction that hit King of Prussia, Bala Cynwyd and Exton a few years ago, there are very few supply concerns in suburban Philadelphia. The approval process in most municipalities is tedious, expensive and challenging. As a result, fewer projects get built, supply and demand remain in equilibrium, and operating fundamentals continue to be very healthy.

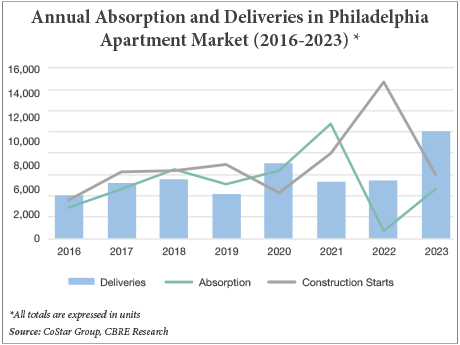

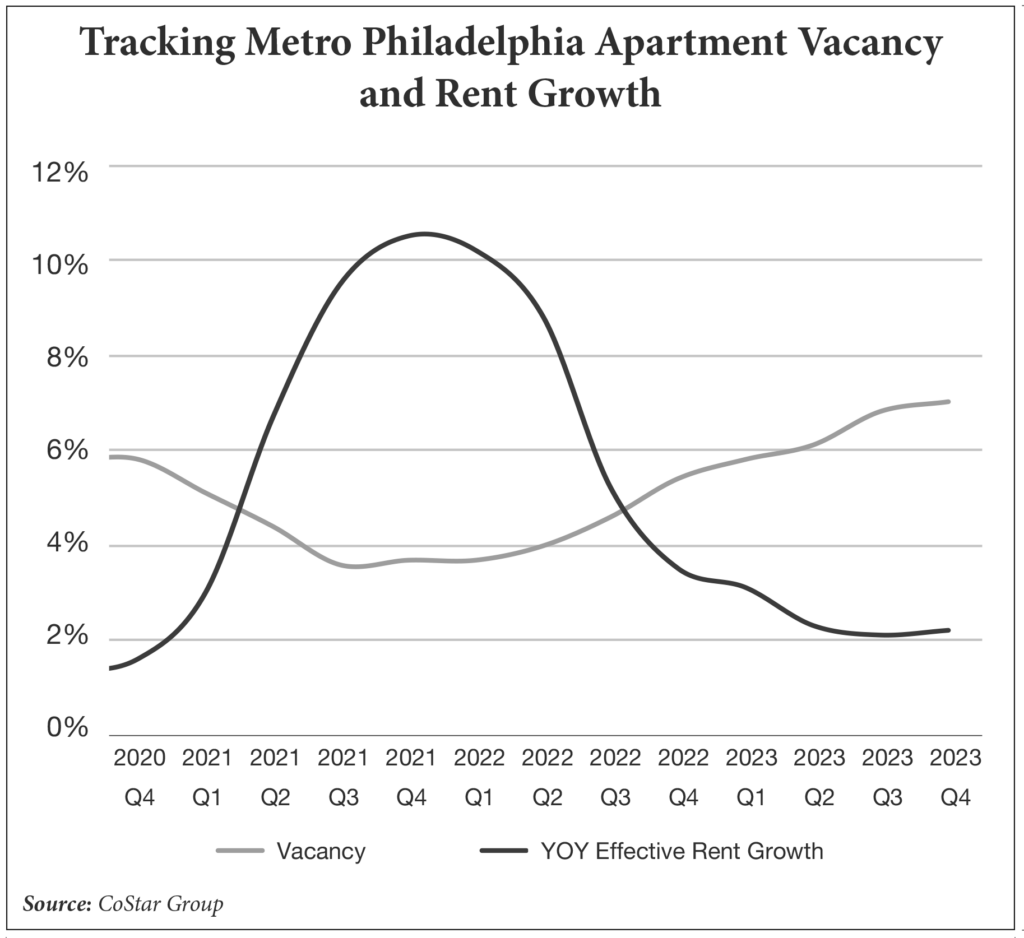

It’s a much different story within the City of Philadelphia, where operating fundamentals have softened, as approximately 14,000 units are under construction or currently being leased up. Many neighborhoods are dealing with numerous multifamily assets in lease-up simultaneously and an abundance of new construction set to be delivered this year.

Winter is always the slowest leasing season, but this past winter proved to be even more difficult for apartment owners in the city, as the new supply added to the challenge. To combat slow leasing and keep buildings well occupied, owners are offering concessions to attract new residents and retain existing tenants.

In some cases, landlords are offering as much as two or three free months of rent to entice prospective residents to move in. This often leads to renters moving from one newly constructed asset to the next to chase the biggest concessions until the entire market stabilizes.

While the long-term trend remains favorable for multifamily assets in Philadelphia, many investors believe that the next 18 to 24 months are likely to be challenging in the city.

Investors Drawn to Suburbs

Given the dichotomy between the city and suburbs in terms of overall performance, we are seeing a divergence in investor interest as well, particularly among institutional investors such as pension funds, life insurance companies, investment banks and REITs. As the suburbs currently possess the stronger real estate fundamentals, they are also attracting the lion’s share of institutional investor capital.

Consequently, transactional activity in the city has been dominated by private equity investors who tend to be entrepreneurial and, in many cases, contrarian. Those investors are looking for distressed opportunities where they can acquire an asset at an attractive basis and hold it for the longer term. More than a few times recently I’ve been told, “Debt is temporary, basis is forever.” This had led to smaller-sized transactions and lower sales volume in the city.

Industry Feeling Financial Squeeze

We are certainly seeing distress, but it’s manifesting in several different ways. The small to mid-sized developers who thought that they were building projects to a 6 to 7 percent yield on cost are finding that the property may not be worth the all-in cost to build it, and their equity is either impaired or even completely wiped out.

In some cases, the project took longer to build than predicted, and the interest expense on the construction loan accrued more than anticipated. Rents may be less than forecast and concessions may be necessary to get the property leased up. Thus, the stabilized pro forma net operating income is below that which was used to secure the construction loan.

Most importantly, interest rates and cap rates are up, and values are down. As a result, many of these developers are going to have to contribute more equity to refinance if they want to hold onto their properties. Otherwise, they’ll be forced to sell by lenders that want to be repaid.

This situation is even more dire if the principal has personally guaranteed the loan. In this scenario, if the lender forecloses and sells the asset at a price lower than the loan balance, it will pursue any deficiency from the borrower to be “made whole.” This is a market-wide problem, but it is exacerbated in the City of Philadelphia by the amount of new supply weighing on rent growth and occupancy.

The Rise of Third-Party Managers

In an environment with challenging market conditions as is the case today, a well-run property management company with experience, a solid reputation, and deep human resources tends to make a huge difference in property performance. With 14,000 units under construction and in lease-up, the distinctions between property managers have become more evident.

When the law of supply and demand favors the owners and there are multiple prospective residents for every vacancy, that pricing power may mask the fact that not all property managers are created equal. As a result, we’re seeing many developers realize today that they should stay in their lane, develop and build properties, and then hire a third-party property manager to lease and manage their assets.

Conversions Easier Said Than Done

The office sector is showing signs of distress due to double-digit vacancies caused in large part by the increase in remote work. Owners of poorly occupied office properties are left with limited options to reposition those assets. The initial knee-jerk response is to convert the buildings from office into multifamily. Among large U.S. cities, Philadelphia is a leader in adaptive reuse office-to-residential conversions.

The reality is most office buildings are not conducive for conversion to multifamily based on physical limitations of the building such as ceiling heights, window lines and the depth of floor plates. In the suburbs, if the site is large enough, most developers would prefer to demolish an office building and construct a brand-new asset rather than execute an adaptive reuse conversion.

So What’s the Good News?

There is an ocean of equity capital on the sidelines waiting to be deployed into multifamily, which remains one of the most desirable asset classes within commercial real estate. The government-sponsored enterprises Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac serve as the ultimate backstop for debt capital. They are the best lending options for a multifamily asset that is stabilized, offering non-recourse loans at competitive leverage levels and at various term and pricing options, including interest-only loans.

Despite continued volatility in the debt markets, well-capitalized investors with track records of success are finding ways to capitalize deals. Nonetheless, inflation has clearly proven to be stickier than most predicted, including the Federal Reserve. Accordingly, we are likely to be in a “higher for longer” interest rate period. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell has recently signaled that, if higher inflation persists, the Fed can maintain the current federal funds rate in a range of 5.25 to 5.5 percent “for as long as needed.” Notwithstanding that, the market just wants visibility. As the volatility dissipates, transaction volume will return.

In addition, the bid-ask spread between buyers and sellers has narrowed enough that we’re back to the negotiating table. A year ago, that gap was too wide to consider marketing certain assets for sale. Many owners offered properties for sale at high prices and didn’t transact. Owners today have begun to acknowledge where buyers see value, and deals are starting to get completed.

Finally, there is a housing shortage of approximately four million residences in this country.

Combined with a limited inventory of homes for sale and stubbornly high values, it’s become very difficult for the first-time homebuyers to enter the market. Inflation has impacted their ability to save down payment money, and the average mortgage payment has doubled. Additionally, homeowners are hesitant to sell their house and replace their low-interest-rate mortgage to buy a new home and lock in a high rate.

While it would be logical to conclude that higher interest rates lead to lower housing values, the opposite has occurred. Higher interest rates have served to reduce the inventory of available homes for sale and support higher values. By raising interest rates to combat inflation, the Federal Reserve has inadvertently created inflation in the housing market.

This confluence of factors supports healthy long-term fundamentals in the apartment market and may even be creating a permanent renter class that no longer believes homeownership is the American dream.

From a business standpoint, this year is off to a much better start than 2023. Sentiment has improved, and the industry is primed for a rebound. Nobody is predicting a banner year in 2024, but it already feels as though we’re in the early stages of a recovery and headed toward a more normalized environment in 2025.

Spencer Yablon is a senior vice president with the CBRE multifamily capital markets team and is based in the brokerage’s Philadelphia and Radnor, Pennsylvania, offices. The team specializes in the sale of multifamily properties on behalf of institutions, pension fund advisers, REITs, private equity firms, developers and lenders. He can be reached at [email protected]. This article originally appeared in the March/April issue of Northeast Multifamily & Affordable Housing Business.